Delivered at the Temple of Enlightenment, Bronx, New York

May 25, 1969, the occasion of the celebration of the birthday of Buddha Shakyamuni

Dear friends:

What are the five eyes?

Buddhism classifies the eye into five categories; namely, the Physical eye, Heavenly eye, Wisdom eye, Dharma eye, and the Buddha eye. It should be pointed out first that the term ‘eye’ used here does not refer to the ordinary human eye. The human eye is but one kind of physical eye. As a matter of fact, the human eye is not the best example of this category. An eagle has eyes which can see much farther than can those of a human. An owl has eyes which are much more sensitive to light than our eyes, and can see things in the darkness that we cannot see.

![]()

Physical Eye

![]()

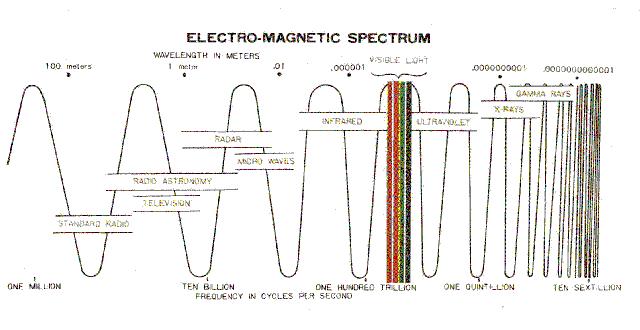

In order to illustrate the limitations of the human eye, I shall use a chart prepared by scientists which is called the electromagnetic spectrum (Chart I). This chart tells us that our naked eye can only see a very narrow strip of the universe, called visible light. We cannot see infrared wave lengths and beyond, nor ultraviolet wave lengths and beyond. This means that before man invented the instruments to assist his naked eye in detecting the universe beyond the visible band, the world that he saw and considered complete, true, and real was actually incomplete and a very small portion of the whole universe. It is really amazing to realize that more than 2,500 years ago Buddha drew this same conclusion without the assistance of any of the instruments we now have.

Chart I

The following example may illustrate more clearly the inferiority of our human eye, and how it compares with the heavenly eye:

Imagine that there is a totally enclosed dark house in the middle of a big city, with one very small window from which one can see only crowded tall buildings, a little blue sky above, and a few limited human activities. Suppose a child is born and grows up in this house. What would be his impressions of his world? They would no doubt be based on what he sees through the small opening. No matter how eloquently one might describe to him the beauty of the vastness of a seascape and the wonder of a view at sunrise and sunset he could hardly understand and appreciate them.

This is precisely how our human eye limits us. We are actually in a dark house, viewing the universe through a very small opening which is our physical eye. Yet we insist that what we see is the complete, real, and true world.

Now imagine that there is another house on top of a mountain. The house has a large picture window from which one can see the unlimited sky and infinite horizon. Maybe we can make it even more romantic by saying that numerous flower gardens and dancing girls surround the place. Again, a child is born and grows up in this house. Is it not conceivable that the world he envisions is much greater and more beautiful than the one seen through the small window facing a crowded city? According to this analogy, the second child possesses the heavenly eye whereas the first one has only the physical eye.

![]()

Heavenly Eye

![]()

Usually it is said that the heavenly eye is possessed by gods or goddesses in heaven. According to Buddhism, however, this statement is not entirely correct because we human beings can also obtain the heavenly eye. There are two ways to achieve it. One way is through ‘dhyana,’ a Sanskrit word which is commonly (but incompletely) translated as ‘meditation.’ The other way is to add an instrument to the naked eye (which is also a kind of instrument that can itself be transplanted). Although the first way, meditation, is a much superior method, the second way is probably easier for modern man to understand. Modern man is able to see into remote space by employing a powerful telescope. Modern man can watch the activities of bacteria by using a microscope. Today, one can observe events happening millions of miles away by means of space vehicles and television, and can see many other wonders which in the Buddha’s time were exclusive to the heavenly eye. In those days, dhyana was probably the only means of enabling a human being to transcend the boundary set forth by the physical eye. It is clear that Buddha realized that although man’s ability to see is infinite, that ability is actually limited by the physical eye. However, through years of meditation, Buddha discovered that the barrier of the physical eye can be broken and that the original ability of man to see can be fully developed. When that occurs, there will be no difficulty in extending one’s vision as far as the realm perceived by the heavenly eye.

Up to this point I believe that you can understand the physical eye and the heavenly eye without difficulty. In Buddha’s time, it was much more difficult for man to understand the heavenly eye; today, practically speaking, everyone possesses the heavenly eye to some degree. It is, therefore, comprehensible to us.

![]()

Wisdom Eye

![]()

Now we come to the wisdom eye.

To describe the wisdom eye we need to introduce a very important and fundamental concept in Buddhism, which in Sanskrit is called ‘shunyata’ and may be translated as ‘emptiness.’ This is a unique teaching that cannot be found in any other religion.

Voluminous scriptures in Buddhism are devoted to the study of emptiness. What I can offer you today is really a drop of water from a vast ocean, but I will try my best. I will introduce to you three analytical modes of thinking, described by the Buddha on many occasions, which lead to the understanding of emptiness:

1. The analytical method of disintegration.

Allow me to use a radio as an example. Imagine that I have a radio here. If I take out the loud-speaker, can you call the loud-speaker the radio? The answer is no. You call it the loud-speaker. Now take out the transistor. Do you call the transistor the radio? Again no, it is the transistor. How about the condenser, the resister, the plastic case, the wire, etc.? None of these parts are called the radio. Now note carefully. When all the parts are separate, can you tell me where the radio is? There is no radio. Therefore, ‘radio’ is simply a name given to a group of parts put together temporarily. When one dismantles it, the radio loses its existence. A radio is not a permanent entity. The true nature of the radio is emptiness.

Not only is the radio emptiness; the loud-speaker is too. If I take the magnet out of the loud-speaker, do you call it a loud-speaker? No, you call it a magnet. If I remove the frame, do you call it a loud-speaker? Again no, you call it a frame. When all the parts are taken apart where is the loud- speaker? So, if we dismantle the loud-speaker, it loses its existence. A loud-speaker is not a permanent entity. In reality, a loud-speaker is emptiness.

Now, this analytical method of disintegration can be applied to everything in the world, and will lead to the same conclusion: Everything can disintegrate; therefore, nothing is a permanent entity. So, no matter what name we call a thing, it is, in reality, emptiness.

Buddha applies the method of disintegration to himself. In his imagination he removes his head from his body and asks if the head would be called the human body or self. The answer is no. It is a head. He takes his arm off his body. Would this be called the human body or self? The answer is again no. It is an arm. He takes the heart out and asks whether this is the human body or self. The answer is again no, which we understand now even more precisely since a heart can be removed from one body and transplanted into another without changing one person into another person. Buddha takes every piece of his body apart and finds that none of the parts can be called the human body or self. Finally, after every part is removed, where is the self? Buddha therefore concludes that not only is the physical body emptiness, but the very concept of self is emptiness.

2. The analytical method of integration.

Although we see hundreds of thousands of different things in the world, man is able to integrate them into a few basic elements. For example, based upon chemical characteristics man has classified gold as a basic element. We are able to name thousands of golden articles ranging from a complicated golden statue to a simple gold bar, but all of these articles could be melted and remolded into other forms. They are changeable and impermanent. The things which remain unchanged are the common chemical characteristics, due to which we call all of these articles ‘gold.’ In other words, all of these articles are integrated under the category of the element which we call gold.

In Buddha’s time, Indian philosophers integrated everything into four basic elements, namely, solids, liquids, gas, and heat. Buddha went further and declared that the four elements could be integrated into emptiness. Continuing with our example of gold, Buddha’s statement means that we can also question the existence of gold as a permanent entity, even though we have recognized it as a common characteristic of the various golden articles. Whatever we can show is but a specific form of gold, such as a gold bar which is basically changeable and impermanent. Therefore, gold is simply a name given to certain characteristics. Gold itself is emptiness.

By the same reasoning, the Buddha concluded that all solids are emptiness. Not only are solids emptiness, but liquids are too, since the characteristics of fluidity are formless, ungraspable, and empty of independent existence. Thus, 2,500 years ago, Buddha concluded that everything in the universe can be integrated into emptiness.

It is certainly interesting to note that Western scientists have reached a similar conclusion. Before Albert Einstein discovered the theory of relativity, scientists integrated everything in the universe into two basic elements, namely, matter and energy. Einstein unified these two elements and proved mathematically that matter is a form of energy. By doing so, he concluded that everything in the universe is simply a different form of energy.

But what is the original nature of energy? Although I would not venture to assert that energy is the same as emptiness, I would at least like to say that energy is also formless, ungraspable, and analogous to emptiness.

3. The analytical method of penetration.

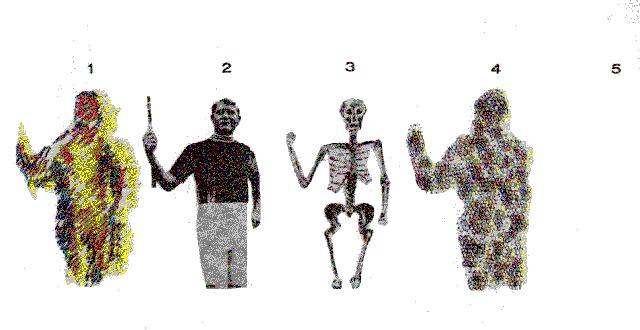

Buddha performed this method by means of meditation. Meditation may be difficult for most of us, but fortunately today’s scientific technology furnishes us with certain analogies which can give us some comprehension of this method. Let us refer back to the electromagnetic spectrum. We know that our naked eye can see only the small portion of the universe which is visible to us, but with the aid of certain instruments, such as an infrared device, x-ray, microscope, etc., modern man is able to see other realms of the universe. To help you understand this more thoroughly, I introduce another chart (Chart II). Here we see an ordinary man as he would be detected by different instruments at different wave lengths. The chart is divided into five sections. Under number one you see an image mainly consisting of red, yellow, and green colors, which is a man as detected by an infrared device. Under two is a man seen by our naked eye. Under three is a man seen through an x-ray apparatus, whereby the skin and flesh disappear but the structure of bone remains. Next to it, marked four, is a picture of the molecular structure of a human body seen microscopically. To the extreme right is an empty space marked five.

Chart II

Please don’t be misled by this chart to think that these various images and the empty space are different entities. They are all the same man. Also don’t be misled into the notion that the images occupy different spaces, from left to right. Actually they are all in the same place. To make it more clear, please suppose that I am the man depicted on the chart. Now just imagine that your eyes are able to detect infrared. What you see standing in front of you is a red, yellow, and green colored image. Now shift back to the instrument you use daily; my external form is perceived by your naked eyes. Next imagine that your eyes can see with an x-ray. My skin, flesh, and blood disappear and what you see now is the bone structure of my body. Changing to another instrument, the microscopic eye, the man standing in front of you is a complicated chain structure of molecules. Now penetrate a bit further. Modern science teaches us that molecules consist of atoms, and atoms consist of particles, and ultimately all mass can be converted into energy, the original nature of which is something that we cannot see or hold. Let’s call it formless form, which is represented by the empty space numbered five on the chart.

Your attention is invited to the fact that I am the same man in the ordinary sense, but that I can appear to you in different forms: colorful image, fleshly body, structure of bones, assembly of molecules, many other forms corresponding to different realms or instruments, and finally the formless form.

This third method, the analytical method of penetration, again leads to the same conclusion that everything in the universe can be penetrated to its foundation, called energy by scientists, and emptiness by Buddha.

Now please note a very important point: My discussion so far has been strictly intellectual. However, emptiness is a state of direct experience. It is said that when one reaches that state there is an experience of tremendous bliss which is hundreds of times stronger than any kind of bliss ever experienced by ordinary man. Furthermore, emptiness is a state in which one transcends the sense of change and impermanence .

Now let me go a step further. As you may know, the realization of human suffering was the direct cause which led the Buddha-to-be, Prince Siddhartha, to renounce his palace and to become an ascetic in search of the way leading to the emancipation of mankind. Buddha listed eight kinds of human suffering, called ‘duhkha’ in Sanskrit, which has a somewhat more extensive meaning than the word ‘suffering.’ The eight sufferings are birth, old age, sickness, death, loss of loved ones and pleasant conditions, association with unpleasant persons and conditions, failure to obtain what one wants, and impermanence. I do not have time to explain the eight sufferings to you in detail, but if you carefully analyze them you can conclude that all eight sufferings are related to, or have originated from, the physical body and consciousness that we call self. The physical body and consciousness of the self are the foundations upon which all human sufferings are built.

Now, if the physical body and the consciousness of self are no longer in existence when the state of emptiness is achieved, how can suffering still exist? When one reaches that stage, everything in the universe, including oneself, is seen as emptiness. All human sufferings disappear, and one is said to possess the wisdom eye.

It’s like sudden relief from a deadly heavy burden. It’s like the unexpected reunion of a mother with her son who had disappeared for years. It’s like the discovery of land on the horizon while one is sailing desperately on a stormy sea. These are a few of the descriptions of the great delights that are experienced when the wisdom eye is gained.

Many disciples of Buddha reached this stage. Such people were called arhats. Although they were saints, Buddha issued a stern warning to them: “Don’t stop at the wisdom eye.” Buddha explained that with the physical or heavenly eye we see the incomplete, changeable, and unreal world as complete, permanent, and real. Thus we become attached to the world, which is why we suffer. This is one extreme. With the wisdom eye we see everything in the universe as impermanent, unreal, and empty, and like to remain in that state of emptiness. This becomes an attachment to emptiness, and is the opposite extreme. Once there is attachment, whether to a substance or to emptiness, the consciousness of self, which is the root of all ignorance and suffering, cannot be completely eliminated. To obtain the Dharma eye is, therefore, the ultimate teaching of Buddha.

![]()

Dharma Eye

![]()

What is the Dharma eye? A man is said to have the Dharma eye when he does not stay in emptiness after gaining the wisdom eye. Instead, he recognizes that although whatever he sees in different realms is only a manifestation, it is nevertheless real with respect to its realm.

Let’s refer to the Chart II again. One who has only the physical eye will insist that only the physical body is real, since he lacks the knowledge of all other realms. One who possesses the wisdom eye sees that these forms are phantoms which are impermanent, insubstantial, and unreal, and that emptiness is the only state which is real and permanent. Thus does one become attached to emptiness.

Now, one who possesses the Dharma eye will say that although it is true that all such forms are manifestations, they are not entities separate from emptiness, and they are real with respect to the realm they are in. This realization automatically generates an unconditional, nondiscriminative universal love and compassion. Such a person is said to possess the Dharma eye; in Buddhism that person is called a bodhisattva.

Once one overcomes the attachment to emptiness, the unconditional, nondiscriminating love and compassion arising spontaneously from a direct experience of emptiness is truly a wonder of mankind. This teaching makes Buddhism a most unique and profound practical religion.

Let me tell you a story to illustrate the difference between an arhat who has achieved the wisdom eye and a bodhisattva who possesses the Dharma eye:

A huge mansion is on fire. There is only one door which leads to safety. Many men, women, and children are playing in the mansion but only a few of them are aware of the danger of fire. Those few who are aware of the danger try desperately to find a way out. The way is long and tricky. They finally get out of the mansion through the heavy smoke. Breathing in the fresh open air again, they are so delighted that they just lie on the ground and do not want to do anything more. One of them, however, thinks differently. He remembers that many people are still inside and are not aware of the danger of the fire. He knows that even if they are aware, they do not know the way that leads to safety. So, without considering his own fatigue and risk he goes back into the mansion again and again to lead the other people out of that dangerous place.

This person is a bodhisattva.

There is another famous Buddhist story which has been introduced to Western readers by Professor Huston Smith in his distinguished book, The Religions of Man.* It goes as follows: Many people are traveling across a desert in search of a treasure at a remote location. They have walked a long distance under the hot sun, and are tired, thirsty, and desperately in need of a shaded place to rest and some water or fruit to quench their burning thirst. Suddenly three of them reach a compound surrounded by walls. One of them climbs to the top of the wall, cries out joyfully, and jumps into the compound. The second traveler follows and also jumps inside. Then the third traveler climbs to the top of the wall where he sees a beautiful garden, shaded by palm trees, with a large pond of spring water. What a temptation! However, while preparing to jump into the compound, he remembers that many other travelers are still wandering in the horrible desert without knowledge of this oasis. He refuses the temptation to jump into the compound, climbs down from the wall, and goes back into the immense, burning desert to lead the other travelers to this resting place.

* New York: American Library, 1958.

I believe that everyone here will have no difficulty in understanding that the third person is a bodhisattva.

It should be pointed out here that such compassion is not superficial but is deep and fathomless. It has no pre-requisite such as “because I like you” or “because you obey me.” It is nondiscriminating and unconditional. Such compassion and love arises spontaneously from the direct experience of emptiness, the state of perfect harmony, equality, and lack of attachment of any sort.

By this point I hope that you have some understanding of the four kinds of eyes. Here is a story about two famous verses in Zen Buddhism:

The Fifth Patriarch in the Tang Dynasty of China once asked his disciples to write a verse to present their understanding of Buddhism. The head monk Shen Hsiu presented one as follows:

The body is a wisdom tree,

The mind a standing mirror bright.

At all times diligently wipe it,

and let no dust alight.

The Fifth Patriarch commented that Shen Hsiu had only arrived at the gate and had not entered the hall.

A layman called Hui Neng was also in the monastery. Although he had not yet received instruction from the Fifth Patriarch, he was nevertheless a highly gifted person. When Hui Neng heard the verse, he disagreed with Shen Hsiu and said, “I have one also.” He submitted this verse:

Wisdom is no tree,

Nor a standing mirror bright.

Since all is empty,

Where comes the dust to alight?

Later, Hui Neng became the Fifth Patriarch’s disciple and achieved enlightenment. He became the famous Sixth Patriarch of Zen Buddhism. He gave different teachings to persons of different capacities. Although there is no such record, I would venture to say that the Sixth Patriarch would have had no hesitation in telling a beginner who requested instruction that

The body is a wisdom tree,

The mind a standing mirror bright.

At all times diligently wipe it,

And let no dust alight.

Now, with what kind of eye did Shen Hsiu present his verse? With what kind of eye did Hui Neng disagree with Shen Hsiu and present his own verse? And why, after he had become Sixth Patriarch would he use the one with which he had disagreed before? What kind of eye was the Sixth Patriarch employing now? I will not answer these questions but would like to leave them with you so that you might find your own answer.

![]()

Buddha Eye

![]()

Now we come to the buddha eye.

So far I have managed to say something to you about the four kinds of eyes, but there is really nothing I can say about the buddha eye because whatever I say will miss the point.

But I also know very well that I cannot just stop here, say nothing, and raise a golden flower like Buddha did. Not only do I not have the kind of radiation to convey understanding through silence, but also you will not be satisfied. It is understandable that just as we all have the physical eye, we all have the physical ear and the physical mind. I therefore have to say at least something.

You will notice that in our discussions about the first four kinds of eyes, there was always a subject and an object. For example, with the physical eye we have a human being as subject and worldly phenomena as object. With the heavenly eye we have divine beings as subject and the vast realms of space as object. With the wisdom eye we have arhat as subject and emptiness as object. Bodhisattva is the subject and the various realms of the universe are the objects when we refer to the Dharma eye. When we talk about the buddha eye, however, it would be quite incorrect to say that buddha is the subject and the universe is the object, because the distinction no longer exists between buddha and the universe. Buddha is universe and universe is buddha. It would be equally wrong to say that buddha possesses the buddha eye because there is again no distinction between the buddha eye and buddha. Buddha eye is buddha and buddha is buddha eye. In short, any duality you can construct is not relevant to the buddha eye.

The second point I wish to make about the buddha eye concerns the nature of infinite infinity. What do I mean by infinite infinity? Although we say that the human concept of the cosmos is an infinity, such a concept is just like a bubble in the vast sea when compared with Buddha’s experience of the cosmos. Is it incredible? Yes, it is incredible. But let’s think of what we have in mathematics. You know that the first degree of power is a line. The second degree of power is a plane. The third degree of power represents a three-dimensional space. All of these shapes could already be infinite in size. Now how about the fourth degree of power, the fifth degree of power, up to the nth degree of power? If you are able to explain what the nth degree of power represents, you might have some understanding of Buddha’s cosmology: the infinite infinity.

Thirdly, I wish to say something about the nature of instantaneity and spontaneity. This is again a concept that is very difficult for human beings to understand. To us, the duration of time is a solid fact. Moving through this time factor, man grows up from an infant, to a youth, to maturity, to old age, etc. It is beyond our comprehension to say that time does not exist for the buddha eye, but that is what the buddha eye entails. Billions of years are no different from one second. A world which is measured as billions of light years away from the earth according to our cosmology can be reached in just one instant. What a wonder this is!

The final point I wish to make about the buddha eye is its nature of totality and all-inclusiveness. Some of you might have seen a movie called “Yellow Submarine.” A monster which is like a vacuum machine sucks in everything it encounters. After it has sucked in everything in the universe, it begins to suck in the earth on which it stands. The vacuum machine is so powerful that it sucks the whole earth into itself and finally it sucks itself in. This image illustrates the all-inclusiveness of the buddha eye.

Now, let me summarize. I have mentioned four points about the buddha eye:

1. no subject and no object; that is, no duality

2. infinite infinity; that is, no space

3. instantaneity and spontaneity; that is no time

4. all-inclusiveness and totality; that is, no nothingness.

These are the four essential concepts of the buddha eye, if we must express it in words.

Before I conclude today’s talk I would like to tell you another story.

A couple was always at odds with each other. Then they heard about the five eyes. One day they began to quarrel. It looked as if it would be one of their usual arguments with both husband and wife so upset, angry, and frustrated that they wouldn’t speak to each other for days. Suddenly the husband said, “I am using my heavenly eye now. You are just a skeleton. Why should I argue with a skeleton?” The wife kept silent for a while and then burst into laughter. The husband asked, “What are you laughing about?” The wife said, “I am using my wisdom eye and you’ve disappeared. Now there is nothing bothering me. I am in shunyata.” Then they both laughed and said, “Let us both use our Dharma eyes. We are all manifestations, but let’s live happily together in this realm.”

Today we are celebrating this great man, Buddha Shakyamuni’s birthday. Reverend Chi Hoi is going to deliver to you a big birthday cake. I am only giving you some birthday candy. My birthday candy is this advice: Don’t always use your physical eye, but broaden your view. Do not let your mind always be carried away by what you see in this narrow band of “visible light.” Break this narrow perception. Broaden your view. Develop and open your heavenly eye. Gradually develop and open your wisdom eye. At that point please remember our numerous fellow men and other poor creatures struggling in the immense burning desert of birth and death. Open your Dharma eye! Eventually I hope that all of you will have the buddha eye, and will reach the highest state of enlightenment so that you are capable of leading the numberless sentient beings in infinite space to buddhahood as well.

Thank you.